If the results are mixed on some points and many NGOs denounce a lack of ambition of the States, this COP is according to many scientists and organizations, a step forward, even if there is still a long way to go. From the point of view of forests, this COP is even a good step forward with a commitment of nearly 20 billion dollars to fight deforestation and restore the world's forests.

The Glasgow Declaration : a reaffirmed commitment to fight deforestation

The first positive outcome of COP 26 remains the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use now signed by 141 countries(1) to halt deforestation and land degradation by 2030. Together, these countries account for 90% of the world's forest cover, or nearly 37 million km2.

In the Glasgow Declaration, the signatory countries affirmed the importance of all forests in limiting global warming to 1.5°C, adapting to the effects of climate change and maintaining healthy ecosystem services. They agreed to "halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, while ensuring sustainable development and promoting inclusive rural transformation."

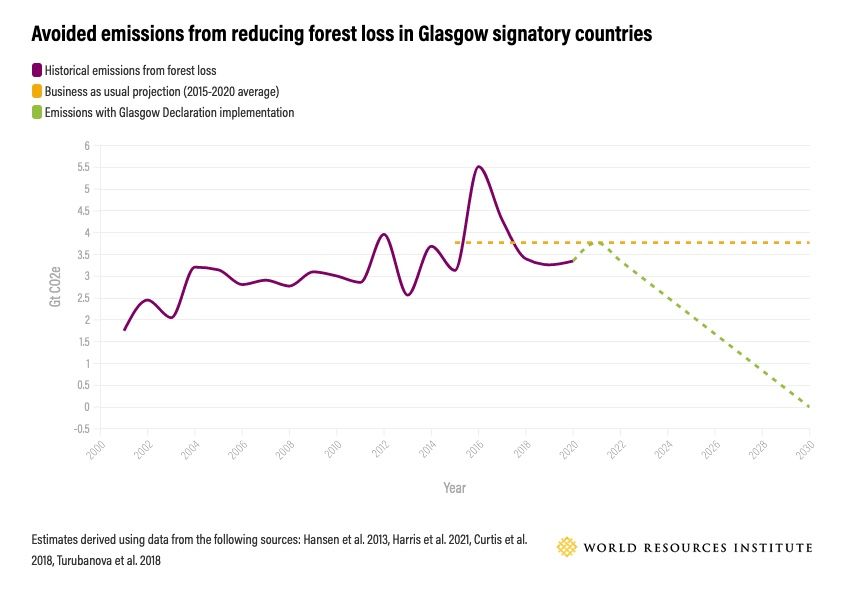

The World Resource Institute (WRI) has projected the avoided emissions (relative to a “business-as-usual” scenario) if the commitments made by the signatories of the Glasgow Declaration were met in full. Stopping deforestation would avoid 18.9 gigatons of CO2 equivalent, or a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions from transportation between 2009 and 2018.

RA's viewpoint: This commitment to stop deforestation and land degradation is not new but it is a strong political signal. It takes up the New-York declaration, which was updated in October 2021 because the signatory stakeholders had not reached the intermediate objectives by 2020. On a positive note, new countries such as Brazil have signed the Glasgow Declaration - although they had not joined the New York Declaration. Today, all the countries that signed in Glasgow cover 90% of the world's forests. From now on, and even if this declaration is not binding, it is essential that this commitment will be implemented to address the twin crises of climate and biodiversity in an urgent manner.

Significant financial pledges for forests

No less important, in addition to the signing of this declaration, many countries and organizations have made financial commitments to forests. A total of $19.2 billion divided between states and private funds were pledged to fight deforestation, protect and restore forests.

12 countries(2) have announced the launch of the Global Forest Finance Pledge (GFFP) of $12 billion in climate finance between 2021 and 2025. These funds will be used to finance activities in developing countries, including the restoration of degraded lands, the fight against forest fires and the defense of the rights of indigenous communities (up to $1.7 billion). In addition to this funding, there is $1.5 billion in special support for the forests of the Congo Basin.

These funds will complement the $7.2 billion in private and public sector funding.

RA's viewpoint: The commitment of private and public actors to the tune of $20 billion is a good thing and shows the importance given by both sectors to the protection and restoration of forests, the fight against deforestation and the defense of the rights of indigenous populations. However, this amount is still far from sufficient and remains promises that must be fulfilled. Indeed, according to the report published by UNEP, the World Economic Forum and ELD, the cumulative investment needs for afforestation and reforestation between 2021 and 2050 are nearly $4700 billion.

The renewed FACT dialogue

Launched in 2021, the Forest, Agriculture and Commodity Trade (FACT) dialogue, co-chaired by the UK and Indonesia, brings together 28 governments from the world's top consumer and producer countries of beef, soy, cocoa and palm oil. The goal of this collaboration is to ensure that these goods can be traded in a way that enhances the socio-economic development of producing countries while avoiding deforestation.

The new FACT roadmap was endorsed at the COP by 25 countries that account for 76% ($350 billion) of the world's exports of soy, palm, cocoa, beef and leather, timber, paper and pulp. To implement this roadmap, the UK has announced just over $670 million in UK funding.

Meanwhile, ten companies, including Cargill, Wilmar and Olam, which handle more than half of the world's trade in so-called "deforestation-risk" products, have committed to developing their own roadmap by COP27 to accelerate action to eliminate deforestation from these products in their value chains.

RA's viewpoint: This new FACT roadmap allows countries to take action to fight deforestation. It is a good initiative that distinguishes itself from previous ones by bringing on board large producer countries such as Brazil and Indonesia, and which has the merit of integrating small producers who are too often forgotten in many resolutions. However, the commitments must be better formalized and monitored over time to ensure their proper implementation.

State climate commitments : despite the improved NDCs, there is still a long way to go to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement

In 2015, the Paris Agreement invited all signatory countries to develop a national plan defining a trajectory for reducing their greenhouse gas emissions: the famous nationally determined contributions (NDC). These NDCs were to be revised upwards after 5 years, i.e. by COP 26.

Following their revision, the ambition of the NDCs has been raised, which is a positive step, even if the contributions remain insufficient to be on a trajectory of limiting the temperature to 1.5°C by the end of the century according to UNEP.

In fact, according to UNEP, which has updated its assessment report, all the updated NDCs would put us on a trajectory of 2.7°C at the end of the century compared to the pre-industrial era (with a probability of 66%), whereas the assessment on the previous climate plans of 2015, was rather based on a rise of 3.2°C.

However, if we also consider the promises of carbon neutrality made in the NDCs, that we do not only look at the trajectories of the necessary reductions in greenhouse gas emissions but also at the forecasts of absorption through the restoration of forests or the creation of new forests for example, then the warming could be limited to 2.1°C in 2100.

In addition, the COP 26 has obtained from the States that they increase their NDC objectives from 2022 and no longer in 2025 as it had been envisaged during the COP 21.

RA's viewpoint: Even if the contributions submitted are still considered insufficient (above 1.5°C by 2100), experts note a general increase in ambition. The objective of limiting warming to 1.5°C by the end of the century must nevertheless remain the absolute priority to maintain the habitability of the Earth for the human species. It is thus urgent that States increase their efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; and even if carbon sinks are a help to achieve carbon neutrality, they must not undermine the emission reduction targets.

Carbon markets : a tense subject but one that offers opportunities

This was one of the last technical items to be negotiated to implement the Paris Agreement. Among the points negotiated during COP 26 was the much debated topic of the rules for implementing Article 6. Since 2015, negotiations had been postponed from COP to COP to finally reach an agreement on carbon markets and non-market approaches in Glasgow.

The objective of Article 6 is to regulate the operation of carbon trading through the creation of markets. This is a particularly important point because, according to the UN, most countries that have submitted their NDCs plan to use the carbon market to achieve their emission reduction targets.

After six years of negotiations, the States established in Glasgow a solid and complete accounting framework for the international carbon markets and various mechanisms for trading and certifying carbon offsets.

Two carbon markets will thus be created: the first open only to States and the second open to the public and private sectors. The second has a particular link with forestry issues because it will allow, under the supervision of the UN, the exchange of carbon credits that can take different forms including forest restoration.

In concrete terms, the operating principle of a carbon market will allow a country or a company to buy carbon credits from a surplus player either to reach its emission reduction targets or to improve its carbon balance by aiming for neutrality.

The subject of carbon markets is a major concern for several international players. These concerns are particularly focused on the fact that the land sector (i.e. forests, agricultural areas, wetlands or grasslands) has been included in the market. In fact, this paves the way to a potentially massive recourse to carbon offsetting via reforestation projects.

As a reminder, carbon offsetting is an approach that aims to finance projects that avoid CO2 emissions or increase carbon sequestration (by planting trees for example), with the objective of contributing to achieving global carbon neutrality.

An Oxfam report published in August 2021 shows that carbon storage programs planned by governments and the private sector already account for "at least 1.6 billion hectares of forests, more than all the arable land on the planet".

RA's viewpoint: The carbon market and, by extension, carbon offsetting, even if imperfect, will be essential to enable countries to achieve their climate objectives, including climate neutrality in 2050. These solutions must be temporary and allow us to move towards a circular bioeconomy, based on living organisms and no longer on fossil fuels. Furthermore, it is necessary to remember that the reduction of GHG emissions at the source is always a priority and that offsetting should only be used as a complement to reduction actions, because without this, the areas available for offsetting would not be sufficient.

(1) : However, Indonesia, a signer of the Agreement, began to backtrack on its commitment a few days later, indicating that its own interpretation of the declaration was to "to reduce deforestation, not completely end it”.

(2) : Germany, Norway, United Kingdom, United States, France, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the European Commission (on behalf of the EU).