All photographs were taken by Florian Pupat on site. Click here to see his portfolio.

The project funded by Reforest'Action is located in the Mexican state of Campeche, one of the administrative divisions that make up the Yucatán Peninsula and border the Gulf of Mexico. This geographical area is rich in historical and natural heritage and deserves special attention.

Strong legacies of the past

Cradle of the Mayan civilization and the Chontal people, the indigenous territory of Campeche resisted Spanish colonization until the year 1540. Reflecting the hostility of the natural ecosystems found there, its native name literally means "place of snakes and ticks". The Spanish occupation, in addition to the major cultural upheaval that resulted, marked the beginning of a massive shift in land use of the region.

The conquistadors cut down the forest of Campeche, once covered by a unique tropical jungle, to cultivate sugar cane and other marketable foodstuffs. This is how the economic interest of some endemic species is discovered. The most striking example is undoubtedly the trade of the Palo de Tinto, an ancient Mayan tree, which heralded the rise of an unprecedented commercial era.

Unspoilt jungle, Campeche State

The Campeche wood: wealth of a bygone era

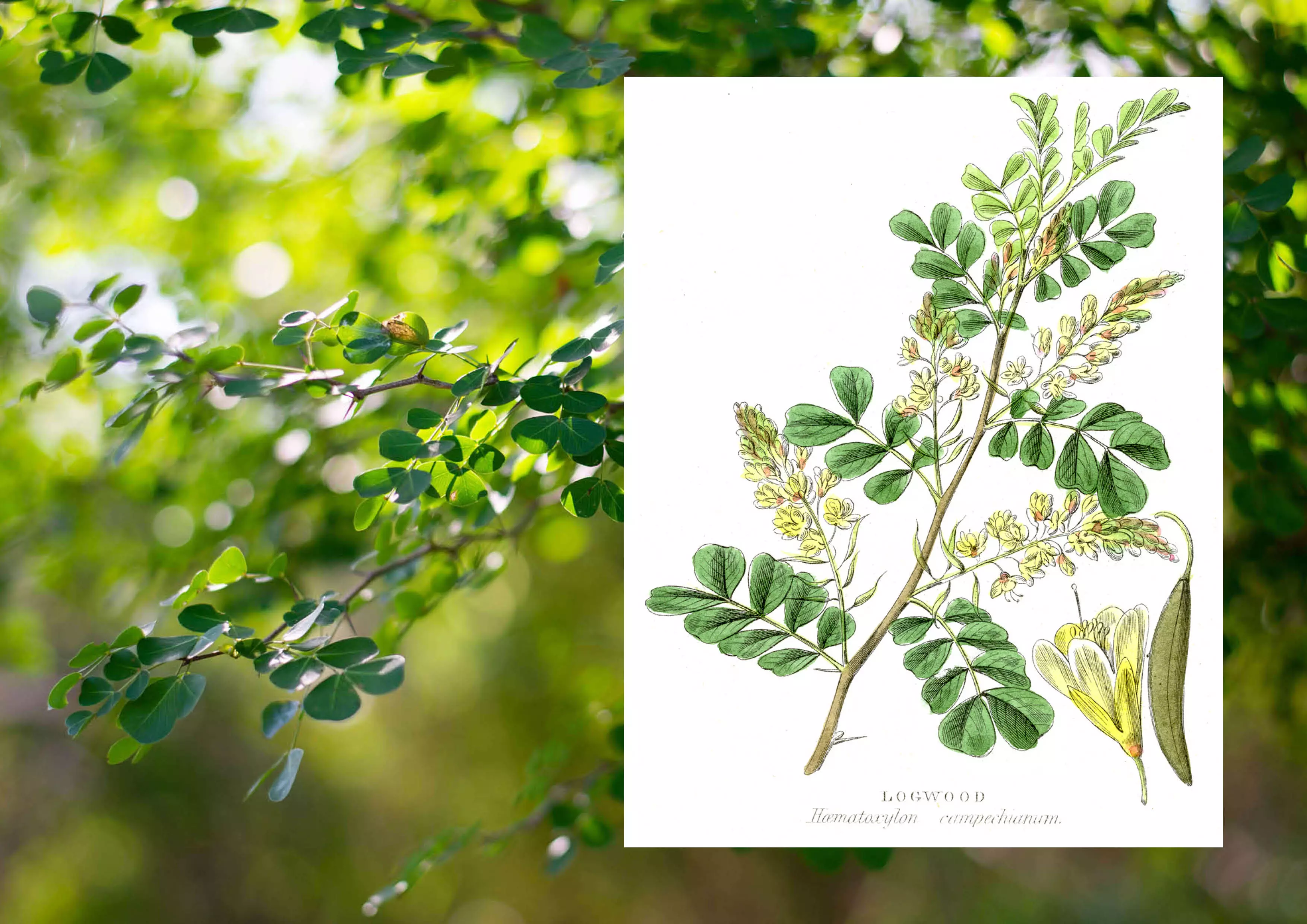

Palo de Tinto - also known as "Campeche wood", "logwood" or "blackwood" - is a small thorny tree from Mexico. Its dark red fibers produce a black ink used for writing on paper, dyeing clothes and hair. During the colonial period, this dye wood was widely exported to Europe by the Spanish, and hematoxylin (the coloring substance contained in the wood) became the most widely used dye on the European continent. Until the 18th century, almost all fabrics, leathers and official documents were impregnated with its red powder. As the gold of Campeche, Palo de Tinto quickly attracted the covetousness of the most legendary pirates, who tried to take over the ships of the Fleet of the Indies.

Branch of Palo de Tinto

Cattle in the shade of palm trees

The industrial revolution, which democratized the use of synthetic dyes, that were way cheaper to produce, meant the decline of Campeche wood. After the independence of Mexico in 1821, the population was forced to find other livelihoods. The growing of rice, adapted to the flooded environment, and the massive breeding of bovines became the main sources of income for local producers. The "cattle boom" caused a major transformation of the landscape, as grass replaced trees. Meat production in Mexico remains a predominant activity today and is a challenge for the conservation and preservation of ecosystems.

It is only at the beginning of the 21st century that the production of palm oil became attractive for breeders whose herds suffered greatly from global warming. Many pastures were gradually converted into oil palm plantations, promoted by the government, which saw this as an alternative to the petroleum economy. The high usage of pesticides in the palm fields has been gradually contaminating the soils and waters of the natural water basins, leading to the disappearance of the incredible biodiversity they shelter.

Currently, nearly 80% of the Campeche state's land has been converted into grazing areas for cattle ranching or into crops for palm oil export.

Oil palm monoculture, Campeche State

A rigorous climate for precious ecosystems

Campeche contains some of the richest natural environments in the world. It is a relatively flat area of sedimentary basins and coastlines. The region's tropical climate is harsh, with high temperatures accentuated by stifling humidity. However, the fauna and flora diversity that subsists in this hostile environment is invaluable. The climatic and geographical conditions of the area are conducive to the flourishing of several types of ecosystems including tropical evergreen forests, grasslands, aquatic and subaquatic ecosystems, mangroves as well as the Tintal biotope (described below).

Located in the heart of the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot, Campeche is home to more than 300 animal species. Among them, the most emblematic are certainly the jaguar, the ocelot (a small feline in danger of extinction), the spider monkey or the howler monkey. In addition, the coastal mangroves play an important role as a sanctuary for migratory birds.

Although the fauna of the region is still abundant, much of it has been wiped out by agriculture and the exploitation of forest resources.

Spider monkey shot in the project area

Tyran quiquivi shot in the project area

Green Iguana shot in the project area

Laguna de Términos

The state of Campeche is located along two important nature reserves: Pantanos de Centlas and Laguna de Términos. The first one is made up of forested wetlands located along the coast, while the second one consists of a natural lagoon, separated from the Gulf of Mexico by a narrow strip of land.

The project developed by our partner is part of the Laguna de Términos protected area. The lagoon has been recognized as an area of high importance since 1994 by the Mexican government because of the richness of the biological ecosystems found in its estuaries. These are fed by several freshwater rivers that flow into the seawater lagoon, giving rise to brackish water. It is the most important lagoon system in the country.

Laguna de Términos Nature Reserve, shot from above

For thousands of years, the sediments transported by the rivers have provided a remarkable habitat for many endemic species. The Usumacinta River, one of the most important rivers in Latin America and probably the richest in nutrients, has enabled a diversity of living organisms to develop. Therefore, in the brackish waters of the lagoon, we can find many aquatic species such as small sharks, turtles and storks, and more than 130 species of mammals including the jaguar, which lives near the water. The vegetation that grows in the reserve offers a breathtaking green landscape.

The humidity that defines this national park makes it very difficult for people to walk through. It rains most of the year and the area is flooded at least six months a year. The water level often exceeds the buildings' height, forcing the local communities to move to the surrounding hills. Alejandra, Project Officer for Reforest'Action in Mexico, describes how difficult it is to get to the project area. "In the dry season, it is only possible to get there on horseback because the vegetation is too high. In times of flooding, we use canoes," she says. In the quarterly report, the field team relates an anecdote: "during the rainy season, the roads were flooded to the point of reaching the bellies of the horses used to carry the staff, and we were able to observe small crocodiles floating near the plantation area."

Canoe transportation in the flooded project area

The Tintal, an unparalleled ecological sink

Between land and sea, the Tintal is the ecosystem in which the Palo de Tinto, or logwood, evolves. Alejandra marvels at this singular species: "it is in fact one of the few specimens that is able to grow with feet in the water, the trunk immersed over dozens of centimeters. If this tree is toxic for many other plants and prevents them from growing in its immediate environment, the blackwood is essential to the survival of many animal species. Indeed, it is a great source of vital nutrients for them. Present only in the Yucatán Peninsula, the Tintal is considered a unique ecosystem in the world.

Immersive journey to the “land of the jaguar”

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the jaguar (Panthera onca) is classified as “near threatened”. With only 64,000 individuals still alive, its population has considerably decreased over the last decades because of the disappearance of its natural habitat. It is estimated that in one century, the fawn has lost half of its range.

Due to the lack of natural prey, the jaguar falls back on domesticated animals, especially on cattle, causing conflicts with farmers who do not hesitate to make it a target. Without shelter or food, the animal is found disoriented, wandering on the surrounding highways where it is regularly hit by vehicles. And that's not counting the poaching which persists in Latin America: the skin and the teeth of the big cat is very appreciated by certain cultures, especially Asian ones. The jaguar is nonetheless very useful to the natural order, since it regulates the populations of herbivores.

In recent years, however, there has been a positive evolution in the number of jaguars in Mexico thanks to conservation efforts in the country. The WWF has recorded a 20% increase in the population over the last 8 years. Yet, the felid is still endangered by the change of land use which does not weaken.

Mexican Jaguar

The jaguar, God of the Maya

The jaguar is one of the most revered animals of the Mayan culture, still clearly noticeable in the Yucatán Peninsula. According to it, considered as the Sun God, the animal has the power to connect the physical world, or "World below", to the spiritual world, or "World above". Perpetuating the cycle of days, it follows the sun's path each morning as it travels across the sky before falling down "below" at nightfall. Symbolizing the sun, the jaguar is therefore seen as the protector of the natural world that links the Maya to Mother Earth.

Today, this powerful feline still plays a significant role in traditional Mexican legends. Annette, Regional Coordinator for Latin America at Reforest'Action, shares with us what she felt during her immersion in the "land of the jaguar": "In the state of Campeche, the jaguar is everywhere and nowhere at once. You hear about it all the time without ever seeing it. It has almost become a myth." It is actually very difficult to spot the animal in its natural environment. "Small cameras were hidden not far from the project, which made it possible for us to joyfully observe the return of this legendary fawn to the conservation area," Annette continues.

Between circular bioeconomy and preservation of wild areas

The project led by Reforest'Action and our field partner is located near the town of Palizada, southwest of Campeche. The lands involved were voluntarily designated to be part of the Laguna de Términos nature reserve. This two-year, multi-faceted project includes different activities with distinct benefits.

The project concerns two areas located side by side: on the one hand, it is about restoring the Tintal endemic ecosystem while, on the other hand, it is a matter of establishing a conservation area that will serve as a refuge for native animal species.

A family-owned business

As part of her visit, Annette met the project leader, Juan-Carlos García, and his German wife, Johanna, who coordinates the operations by his side.

Juan-Carlos inherited the ranch from his father, a former "ganadero" who raised competitive bulls, a very popular discipline in Mexico. After studying permaculture in London, where he met Johanna, he decided to take over the family ranch in order to carry out restoration and conservation activities. He then founded his own company, Planalto, whose multifunctional model allows him to act for the ecosystems while generating a range of by-products from which he reaps the benefits. A virtuous system for the environment and for the local economy. Interviewed by Annette on site, Juan-Carlos is proud of what he is doing: "here, we intend to plant more than a million trees of local species, on a surface of 1500 hectares", he states.

Juan-Carlos and his wife, Johanna

Santa Lucia Ranch

Planalto is staffed by both temporary workers for the simplest tasks and long-term employees trained in the principles of permaculture, holistic management and agroecology. On the ranch land, no pesticides are used, and the soil is not tilled. For Annette, "the vision of Juan-Carlos and his wife is remarkable. They are visionaries."

Workstream 1: restoring the Tintal Ecosystem

On the 1180 hectares that make up the Santa Lucia ranch, Juan-Carlos is working to regenerate the Tintal by planting Palo de Tinto in the degraded pastures. Guacimo, one of the few trees that grows naturally in association with Campeche wood, is also being introduced. Replanting these two endemic species of the region will eventually bring a true forest back to life on these lands, while restoring a unique ecosystem.

Palo de Tinto planting area

Nursery of the project

Palo de Tinto seedlings in nursery

For now, on a small scale, the project generates its own income through the extraction of hematoxylin, which is sold locally to produce dye. The logwood plantings, which are exploited in accordance with a sustainable management process, aim to revive the natural dye market, which has disappeared since the advent of synthetic dyes. In this regard, Juan-Carlos emphasizes his desire to "restore the commercial value of this historically renowned tree."

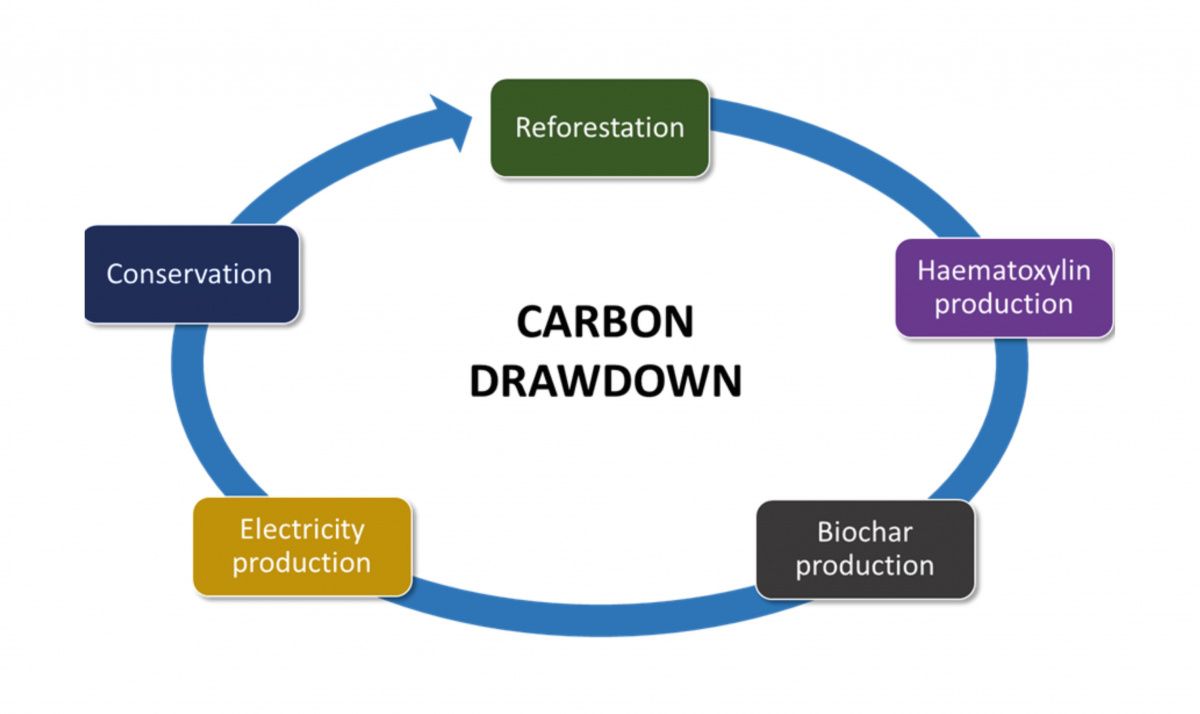

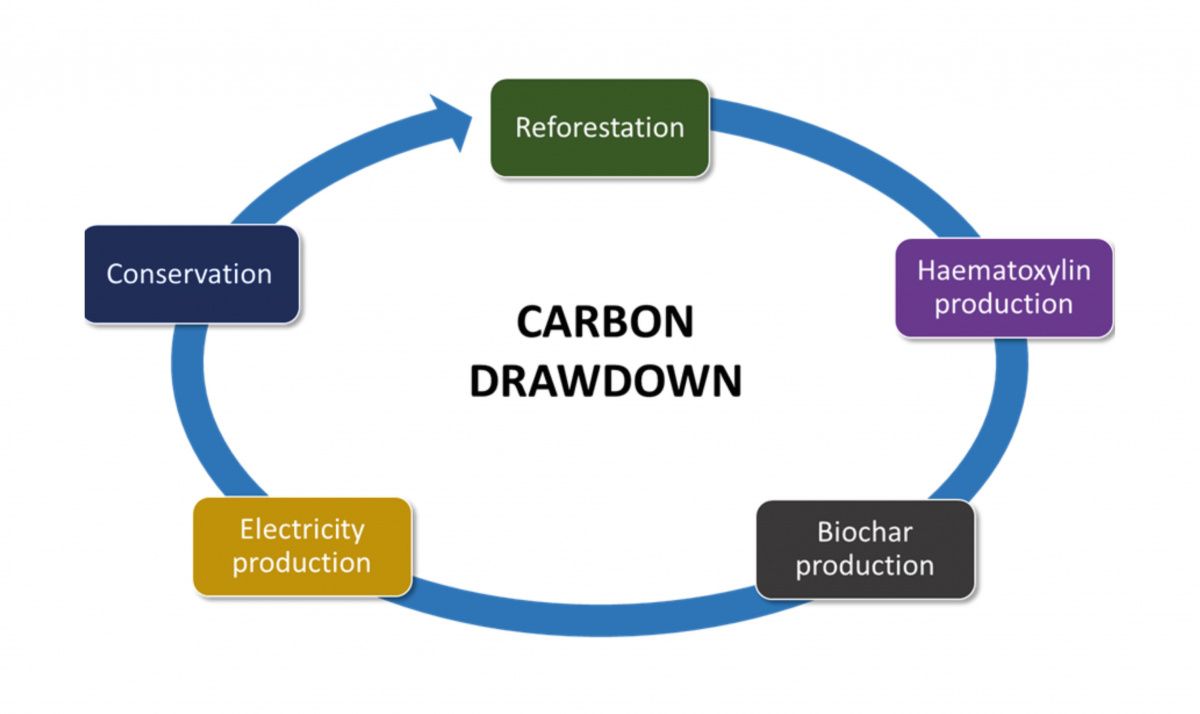

A circular bioeconomy example

Juan-Carlos plans to go one step further. Based on a circular pattern, he seeks to transform wood chip residues into biochar, which he will incorporate into the ground to improve the structure of the soil. The "biochar" is obtained from a pyrolysis process during which the biomass is carbonized at high temperature.

In addition to increasing soil fertility, thanks to its high porosity, biochar enhances water and nutrient absorption by reducing leaching. Though, the main benefit of biochar lies in its ability to increase the amount of carbon sequestered in the soil and to guarantee its long-term storage, i.e. between 500 and 1000 years. With the contribution of Reforest'Action, Planalto expects to capture 1 million tons of CO2 per 10-year cycle.

The heat released during the pyrolysis process can be reused by Juan-Carlos to produce electricity, thus generating a clean and renewable energy. The co-production of biochar and bioenergy contributes to the fight against climate change by being an alternative to the use of fossil fuels. The CO2 released by these transformations will then be stored by the planted trees. "We will give back to the earth what we took from it in the first place. The loop will be closed", claims Johanna, in charge of the project.

Logwood chip

Ink obtained from the extraction of hematoxylin

Bioeconomy defines the valuation of renewable biological resources to produce those needed by humankind (food, materials, energy). In short, it is the same as a circular economy but applied to biomass. Through their pioneering project, Juan-Carlos and Johanna are creating their own circular bioeconomy system.

Workstream 2: restoring Volet 2 : preserving the jaguar habitat

Within his second ranch, named Villa Rosa, Juan-Carlos has established a conservation area in the untouched jungle, with a dedicated area of 350 hectares. In concrete terms, this consists of enriching certain plots by planting a large number of species native to the region, such as the sapodilla, while encouraging the natural regeneration of the forest. The objective is to create a continuous forest cover, which favors the circulation of animals. This approach will also promote the creation of an ecological corridor leading to a river, providing a valuable source of water for wildlife. The planted trees will also generate food for the local biodiversity, encouraging its settlement.

The establishment of this preservation area will have major positive impacts on biodiversity by protecting the natural habitat of various species such as the jaguar, the ocelot and the spider monkey.

Ocelot shot in the project area with a camera trap

An audit mission as challenging as rewarding

In August 2021, Annette traveled to Mexico to audit Juan-Carlos' project. Due to drought, caused by the late rainy season, not all of the 80,000 trees could be planted during the first season. This was eventually rectified. The excess sunshine of the last few months, combined with the lack of water caused by deforestation in the region, lowered the survival rate of the plantings to 80%.

All in all, this field audit mission was full of emotions. Annette confides that the tough climate made her trip "physically demanding". In this respect, she underlines the courage of the couple who carries the project under exhausting conditions. "The technical setbacks and the severe weather they face do not facilitate their activities, but these two people believe in their project," she insists. She concludes by reminding us that "if the environment of Campeche has become hostile, it is in part because man has upset its balance. The goal of Juan-Carlos and his wife is to restore it.

Annette during the audit mission for Reforest'Action in Mexico

Local communities integrated into the project

The state of Campeche, where 60% of the population lives below the poverty line, is one of the poorest in Mexico. That is why the social dimension is a fundamental part of the project.

The implementation of responsible and sustainable forestry practices appears to be a key solution to the socio-economic challenges faced by local people. "In concrete terms, the project provides jobs for local people and contributes to their livelihoods through the sale and direct use of co-products coming from the trees, such as timber," says Juan-Carlos. Tree planting thus benefits the economic development of the populations.

The passing of knowledge: a milestone

It is crucial for the project leaders to involve the inhabitants of the region in the activities carried out on the ranch. Johanna and her husband attach great importance to learning and rural development.

In this sense, Planalto supports and supervises the creation of a school within the project area. The purpose of this school is to teach the children of workers and neighboring families the sustainable methods used in the field, and thus transmit to the youngest the basics of a nature-based agriculture.

The families associated with the project are also trained and made aware during workshops organized by our partner. They learn, for example, how to design and maintain their own organic garden or how to produce compost at home using the Japanese Bokashi method.

Another difficulty encountered with the project is related to the staff hiring process. The competition from the surrounding oil palm groves is fierce. In a context of intensive agriculture, it is very complicated for Juan-Carlos to convey his pioneering vision among his neighbors who have different objectives. Given the tense local economic context, it is essential to retain staff, both through value-added training and through moments of celebration and reward. For example, all employees received first-aid training and were introduced to hands-on techniques designed to avoid the use of herbicides or motorized equipment.

Waste management: everyone's responsibility

Very little waste is left over from the project. All activities have been designed to ensure their recovery by employees. Organic waste is degraded into compost and reused in the tree nursery. For the rest, seedlings are grown in reusable trays while plastic bags are kept and distributed to workers. Dry toilets are made available to everyone. Finally, soda cans and plastic bottles are prohibited on the project.

It should be noted that there is no public waste collection at this location. Traditionally, they are burned in the open air or buried. It is therefore a real step forward for the population to observe and participate in environmentally friendly waste management.

To protect the young trees from African invasive mice, plastic bottles are collected by villagers and cut in half to be placed around the tree trunks. As with pesticides, the use of poison is prohibited.

Local communities integrated to the project

According to Juan-Carlos, "the multifunctional approach of the project is what makes it special. By according similar priority to the biological, economic and social value of the activities carried out, we have succeeded in devising a holistic concept.

In order to fulfill such an ambition, the support of Reforest'Action is key. Johanna does not hesitate to point this out: "We are very grateful to be in partnership with Reforest'Action, because we deal with so many challenges on a daily basis." Annette's visit to the field not only enables the French team to follow up on the various aspects of the project, but also to maintain a strong relationship with the project's stakeholders.

For Johanna, it is also an opportunity to export Planalto's model outside of Mexico: "Thanks to Reforest'Action, we can reach more people, and make them understand what we do and why our work is so important," she adds. "In the current climate context, which is always bad news, people need to know that innovative projects that can make a difference exist," she says, her eyes sparkling.

Palo de Tinto seedling